Today’s Israel is a vibrant kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, tastes, ideas, people, and cultures. Often when teaching Israel, we focus on facts and events, ignoring the dynamic and intense life that is lived. By engaging with the world of arts and culture, however, we are presented with an ideal vehicle for exploring a vibrant vision of Israel.

Arts and culture provide a reflection on the heart of the people and the pulse of society; they bring to the surface themes and ideas that may not find expression in other ways. They frequently serve as commentary on a particular culture by showing an x-ray of life under certain circumstances at a given time and place. The artists who comment on Israeli culture and society through visual art, literature, poetry, film, dance, music, theater, and other artistic expressions provide the educator with material to delve into Israeli society in a way that speaks not only to the minds of students, but also to their hearts and souls. It is through the common language of art—a language not always verbal—that one gets a hands-on appreciation of a society in the deepest sense.

As a result of the subjectivity in their exploration of a theme and the multiplicity of interpretations they offer, arts and culture provide...

Read More

Today’s Israel is a vibrant kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, tastes, ideas, people, and cultures. Often when teaching Israel, we focus on facts and events, ignoring the dynamic and intense life that is lived. By engaging with the world of arts and culture, however, we are presented with an ideal vehicle for exploring a vibrant vision of Israel.

Arts and culture provide a reflection on the heart of the people and the pulse of society; they bring to the surface themes and ideas that may not find expression in other ways. They frequently serve as commentary on a particular culture by showing an x-ray of life under certain circumstances at a given time and place. The artists who comment on Israeli culture and society through visual art, literature, poetry, film, dance, music, theater, and other artistic expressions provide the educator with material to delve into Israeli society in a way that speaks not only to the minds of students, but also to their hearts and souls. It is through the common language of art—a language not always verbal—that one gets a hands-on appreciation of a society in the deepest sense.

As a result of the subjectivity in their exploration of a theme and the multiplicity of interpretations they offer, arts and culture provide students with a nuanced experience and a unique understanding of Israel. There is no black or white when examining a piece of art, reading a poem, or listening to music; this kind of exploration allows multi-faceted beliefs, approaches, opinions, and feelings on the subject of Israel. Just as life exists beyond the scientific and intellectual realm, so do our students, who react with curiosity and excitement when presented with the world of arts and culture.

The philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey noted that art expresses the life of a community.1 By exploring Israeli art we open for our students a world of wealth and allow them a taste of Israeli society at a particular time and place, as well as a taste of the past. While culture evolves over time, certain traditions within a culture remain over many years, and as such, the culture of a community says much about its people, their beliefs, and their aspirations.

Growing up in the United States and studying its history and culture, students are often presented with works of art that illustrate the visual and intellectual flavors of different eras. They might encounter the poem “I Hear America Singing” by Walt Whitman, which celebrates American workers; The Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright; the painting Portrait of the Artist’s Mother by James McNeill Whistler; illustrations of idyllic small-town America by Norman Rockwell; the anthem of the U.S. civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome;” pop art by Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol; and present-day hip-hop music and graffiti art. These iconic examples paint a picture of American societal history as observed through artistic prisms.

How will we create similar experiences for our students around Israeli history and society? How will we touch their hearts and minds?

How We Put the I in Identity

To illustrate the potential of Israeli arts and culture as a means to engage and affect our students, we must explore a theme that is universal, personal, and relevant to their lives. Through Israeli artistic prisms, we can examine the concept of identity and ask questions that are the core of Jewish education:

- What is Israel’s place in the identities of American Jewish students?

- How do these students connect to Israel, its people, and its culture?

- Do these students see themselves as members of a larger community?

- How might these students come to view Israel as their own?

As we examine oral and visual texts, we will explore ways in which individual writers, musicians, and visual artists have asked about their own complex identity, sense of belonging (or alienation), and what, for them, constitutes home. Through their art, we learn that the many factors that inform their answers—factors such as religion, gender, history, and ethnicity—also inform our answers to these questions.

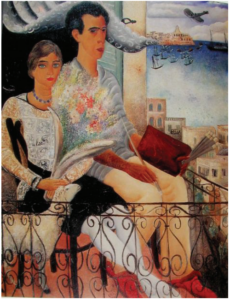

The Engaged by Reuven Rubin

In this 1929 self-portrait of Rubin with his soon-to-be bride, we observe a visual duality of East meets West and urban meets rural. The couple is situated on a balcony overlooking the urban landscape of early Tel Aviv. Rubin dressed the characters in European attire with native or oriental hints portrayed in a flowery scarf around the groom-to-be’s shoulder. Rubin portrays the couple’s connection to the land and the settling of Eretz Yisrael by the lamb sharing their tight sitting space.

In this 1929 self-portrait of Rubin with his soon-to-be bride, we observe a visual duality of East meets West and urban meets rural. The couple is situated on a balcony overlooking the urban landscape of early Tel Aviv. Rubin dressed the characters in European attire with native or oriental hints portrayed in a flowery scarf around the groom-to-be’s shoulder. Rubin portrays the couple’s connection to the land and the settling of Eretz Yisrael by the lamb sharing their tight sitting space.

“Oren” (Pine) by Leah Goldberg

In her poem “Pine,” written shortly after her arrival in pre-state Israel in 1935, Leah Goldberg expresses homesickness and longing for her native Russia while residing in a new homeland. With metaphors from nature, Goldberg conveys the pain of being uprooted and planted in the new soil of a different landscape, and of hovering between two beloved homelands, forever unsettled. At the time the poem was written, such a sentiment was not at all popular; the national Zionist ethos of homecoming expected Jewish immigrants to Israel to shed their Diaspora mentality and memories, immerse themselves in their new society, and embrace a new identity as a new Jew in a new land.

Here I will not hear the voice of the cuckoo,

Here the tree will not wear a cape of snow,

But it is here in the shade of these pines

my whole childhood reawakens.

The chime of the needles: Once upon a time

I called the snow-space homeland,

and the green ice at the river’s edge,

was the poem’s grammar in a foreign place.

Perhaps only migrating birds know

suspended between earth and sky

the heartache of two homelands.

With you I was transplanted twice,

with you, pine trees, I grew,

roots in two disparate landscapes.

“Shir Kniya be’Dizengoff” (A Shop on Dizengoff) by Erez Biton

Erez Biton, who immigrated to Israel as a child from Morocco and grew up in the development town of Lod, conveys another kind of ambivalence towards his place in Israeli society. In this poem, he is torn between the reality of his childhood home in rundown housing projects in Lod and Tel Aviv’s Café Roval, known for its bohemian, intellectual, and celebrity clientele. His attempt to fit in and become a true Israeli—by buying a shop on Dizengoff Street in order to strike a root and belong to the predominantly Ashkenazi mainstream society—proves futile. He feels alienated not only by the elitist, pretentious in crowd that sits in Roval, but also by his own language, one that betrays him by revealing his roots and exposing him as an outsider in his own land.

I bought a store on Dizengoff

In order to strike roots

In order to buy roots

In order to find a place at Roval’s

But

The people at Roval

I ask myself

Who are the people at Roval

What have the people at Roval

What goes with the people of Roval

I do not address the people of Roval

When the people at Roval address me

I pull out my speech

Clean words,

Yes sir,

Please sir,

A very up-to-date Hebrew,

The buildings which stand over me here,

Tower over me here,

And the doors that are open to me here

Are impenetrable to me here

At a dark hour

In a store on Dizengoff

I pack belongings

To return to the outskirts

And the other Hebrew

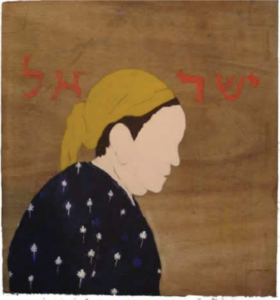

Fortuna 1 by Ronit Chernika

In a series of paintings entitled Family (2001-2005), artist Ronit Chernika presents mainly female figures that lack facial features and therefore lack an individual identity. Other elements of identification are used to create representations of different sectors of Israeli society.

In Fortuna 1, it is the artist’s mother who serves as model and inspiration for the piece. Painted on simple plywood, her faceless portrait is still recognizable as a middle-aged, heavyset woman wearing a simple dress and head kerchief, suggesting she is traditional, possibly Sephardic. The word “Israel,” written in the same manner and similar font as on the Emblem of the State of Israel, connotes that this, among many others, is a representation of Israeli identity. It could be the case that in her creative work, Chernika is observing the official collective Israeli identity, and tries to present alternative identities that make up this multicultural nation.

“Elohay” (“The Lord My G-d”) by Kobi Oz

… I have so much to tell you

yet you know everything

I have so many requests of you

but you anyway want the best for me

I give you a little smile

for everything of beauty I notice

impressive or delicate…

While we, as Jewish educators, are wondering about the place of Israel in North American Jewish identity, many Israelis are exploring the place of Judaism in their Israeli identity. For decades, there was a clear line of separation between the religiously observant and the secular, with nonobservant Jews mostly refraining from embracing more than just the basic Jewish rituals and being resistant to the study of traditional text. In the past few years, there has been a renewed interest in Judaism among secular Israelis, who are rediscovering and embracing Jewish heritage and learning.

Artists are no exception to this phenomenon, and they express this search for Jewish meaning in all media. Musician Kobi Oz recently released an album Psalms for the Perplexed—a result of explorations of his relationship with Jewish texts, beliefs, and family traditions in conjunction with contemporary life in Israel. In his song “Elohay,” he pays tribute to his late grandfather, Rabbi Nissim Messika, who was a religious poet/rabbi in his congregation in Tunisia. Not long after his grandfather’s death, Oz discovered old cassettes that Messika had recorded, and he integrates them seamlessly into this song.

Natala (Netilat Yadayim cup, container for washing hands) by Roie Elbaz

An exhibition at Beit Hatfutsot entitled Judaica Twist reveals how product designers and other artists of applied art deal with similar questions regarding their connection to Judaism. As part of this exhibition, artist Roie Elbaz designed a container for the ritual hand-washing which mimics a military jerrycan used primarily for carrying fuel. The jerrycan is beautifully carved with traditional Hebrew lettering spelling natala, declaring its purpose, and army dog tags hanging from one of its two handles. By sanctifying an object associated with the military, Elbaz is commenting on the central role of the military in Israel and how it filters into all parts of Israeli culture and society, religion being no exception. The colors of blue and khaki that he uses symbolize the combining of kodesh and chol (sacred and mundane), Judaism and militarism, and religion and secularism.

An exhibition at Beit Hatfutsot entitled Judaica Twist reveals how product designers and other artists of applied art deal with similar questions regarding their connection to Judaism. As part of this exhibition, artist Roie Elbaz designed a container for the ritual hand-washing which mimics a military jerrycan used primarily for carrying fuel. The jerrycan is beautifully carved with traditional Hebrew lettering spelling natala, declaring its purpose, and army dog tags hanging from one of its two handles. By sanctifying an object associated with the military, Elbaz is commenting on the central role of the military in Israel and how it filters into all parts of Israeli culture and society, religion being no exception. The colors of blue and khaki that he uses symbolize the combining of kodesh and chol (sacred and mundane), Judaism and militarism, and religion and secularism.

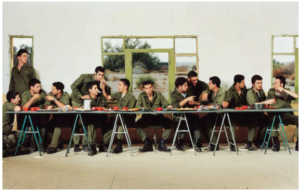

Untitled (The Last Supper) by Adi Nes

Israeli photographer Adi Nes deals directly with the issues of identity in many of his works, tackling difficult subjects like homelessness, homosexuality, life in the army, and soldiers. In one of his most famous pieces Untitled (The Last Supper), he reimagines Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper with Israeli soldiers taking the roles of the twelve Apostles and Jesus. For Nes, every detail is carefully staged to the last detail, so when he inserts an additional soldier in this scene famous for having precisely thirteen people in it—it is deliberate. The additional soldier is watching the scene, causing us to wonder: Who is he? Who does he represent? There is an uneasy feeling lingering in this scene of fraternal camaraderie so typical of the macho Israeli army where eighteen-year-olds face the knowledge that they may never see their next birthday. “I wanted to express the idea that in Israel, death lingers,” says Nes.2

Israeli photographer Adi Nes deals directly with the issues of identity in many of his works, tackling difficult subjects like homelessness, homosexuality, life in the army, and soldiers. In one of his most famous pieces Untitled (The Last Supper), he reimagines Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper with Israeli soldiers taking the roles of the twelve Apostles and Jesus. For Nes, every detail is carefully staged to the last detail, so when he inserts an additional soldier in this scene famous for having precisely thirteen people in it—it is deliberate. The additional soldier is watching the scene, causing us to wonder: Who is he? Who does he represent? There is an uneasy feeling lingering in this scene of fraternal camaraderie so typical of the macho Israeli army where eighteen-year-olds face the knowledge that they may never see their next birthday. “I wanted to express the idea that in Israel, death lingers,” says Nes.2

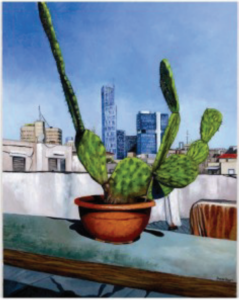

Cactus by Durar Bacri

Bacri, an Israeli Arab born in Acco, depicts his landscape as a busy, somewhat ugly urban area which he observes from his rooftop. In this piece, he paints the view from his apartment in South Tel Aviv, a neighborhood which is home to many foreign workers. Ironically, the metaphor for Israeli born Jews, the Sabra (cactus pear in Arabic)—prickly on the outside, sweet on the inside—is also an Arab symbol of resilience and tenacity, and is a natural fence that keeps in livestock and marks the boundaries of family lands. In many of his paintings, Bacri situates the cactus on the boundary or ledge of the roof. This may symbolize boundaries, but in his case, the cactus might also stress the fact that this is his home—albeit a temporary one—just like a portable plant. Bacri states, “My paintings are made by melting ideology, politics, biology, geography all together and translating them into a new reality that can exist only in my works.”3

Bacri, an Israeli Arab born in Acco, depicts his landscape as a busy, somewhat ugly urban area which he observes from his rooftop. In this piece, he paints the view from his apartment in South Tel Aviv, a neighborhood which is home to many foreign workers. Ironically, the metaphor for Israeli born Jews, the Sabra (cactus pear in Arabic)—prickly on the outside, sweet on the inside—is also an Arab symbol of resilience and tenacity, and is a natural fence that keeps in livestock and marks the boundaries of family lands. In many of his paintings, Bacri situates the cactus on the boundary or ledge of the roof. This may symbolize boundaries, but in his case, the cactus might also stress the fact that this is his home—albeit a temporary one—just like a portable plant. Bacri states, “My paintings are made by melting ideology, politics, biology, geography all together and translating them into a new reality that can exist only in my works.”3

Anatomy of a Conflict by Yossi Lemel

Yossi Lemel, Israel’s foremost graphic artist and poster designer, nails this dichotomy of narratives by dissecting the symbolic cactus pear on the surgeon’s table. An open-heart surgery, if you will. Lemel sees himself as an X-ray technician, someone who reflects on the condition or situation of a patient. In this case, Lemel diagnoses the condition of a society in order to create awareness and hopefully inspire action.

Srulik

.

.

In order to examine what was believed to be typical Israeli identity, we turn to the mythical Israeli-born Sabra. The first native Israelis in a new land saw themselves as a new breed of Jew: free, young, direct, innocent, and patriotic. A well-known artistic and symbolic representation of the Sabra was published in the daily Ma’ariv in 1956, when Srulik (“little Israel”) was born. Illustrator and caricaturist Dosh (Kariel Gardosh) gave him several items characteristic of the Sabra: shorts, biblical sandals, and a “Tembel hat” (dunce cap). For the next forty-four years, until his death in 2000, Dosh continued to comment on Israeli life, society, and politics through Srulik, who remained forever young.

Several decades later cartoonist Dudu Geva, known for creating characters that are the antithesis of the innocent and sweet Srulik, gave his rendition of this mythic Sabra in a tribute to Dosh. In this cartoon, Srulik is depicted as an overweight, middle-aged couch potato, losing his eternal youthfulness.

In 2008, the postal service announced a competition for a 60th anniversary postal stamp featuring a representation of the “typical Israeli.” The competition, won by illustrator Eli Kameli, drew much criticism for promoting a redesign of the irreplaceable Srulik and the very idea that there even exists a “typical Israeli.”

Street Art and Graffiti

The walls are talking to you in neighborhoods across Israel. The popular global phenomenon of street art and graffiti caught on in Israel several years ago and artists have transformed many inner city streets into an outdoor canvas for their art and opinions. Walking through these streets and enjoying the clandestine oeuvres is not the whole story behind that genre. While many of the works could be universally understood, a distinct local flavor emerges upon closer examination. Many of the artists declare their identity, and address historical, political or social issues; street and graffiti artists are making a statement and creating a visual public forum for interaction, dialogue, and sometimes banter. The very nature of street art is its transience and therefore its need to be relevant and succinct in real time. Encountering street art and graffiti, whether it is in an urban area or on the separation wall, is the visual manifestation of the artists’ diverse identities and the country’s zeitgeist.

Rabin’s Assassination Graffiti in Florentine

Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995 sparked a huge public mourning that took the form of candle lighting and public graffiti on the walls around what is now Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. The walls, drawn mostly by adolescents and youth, were later painted over leaving but a small portion of the graffiti aptly saying “Slicha” (forgiveness). They serve as a testament to a generation’s expression of their grief in their own distinct way. Approximately a year later, on a large concrete structure in Tel Aviv’s Florentine neighborhood, Yigal Shtayim painted an ominous black and white graffiti version of the assassination, based on a well-recognized home video that documented this pivotal moment—a moment that is etched in the nation’s collective memory. Unlike most street art, which by nature has a short life, this one is still there thanks to the public’s insistence and the respect of other artists.

Poetic-Graffiti

“If the future turns into present it seems that my greatest fears are happening right now”

The hole

becomes smaller and smaller

and doors

shut in my face

my name is not

Alice

and this is

not

Wonder

Land

A unique combination of Hebrew poetry and street art might reach out from a small alley and deliver a message. Nitzan Mintz says she has a million things to say. Her succinct poetry and images are publicly published and address a wide range of issues: personal, political, and philosophical — sometimes all at the same time. The medium affects the message and therefore the poems are short, in broken verses, without punctuation or title. They declare an idea on a wall or a tree and lets bypassers glance at it or take a second look and ponder on its deeper meaning.

Shirey Moledet | Songs of the Homeland

“Kan” (Here) by Uzi Chitman

…Here I was born,

here my children were born

Here I built my home with my own two hands

Here you are also with me

and here are all of my thousand friends

And after two thousand years

an end to my wandering…

We will conclude our case study by examining the song “Kan” (Here) by Uzi Chitman, which won third place at the 1991 Eurovision Song Contest. It starts with the same word as Leah Goldberg’s poem “Pine,” and therefore closes a circle. Songwriters are no longer writing Shirey Moledet (Songs for the Homeland), once the staple of Zemer Ivri (Hebrew songs). Today, any love songs for the homeland have an element of protest or lament for lost innocence. Uzi Chitman’s song brilliantly leads us from the personal to the national and to Klal Israel (the Jewish people), and serves as a reminder of who we were and what we could still become. “Here” is where we still are, and “there’s no other place in the world” for us—whether we reside in it or hold it in our hearts.

Soon after the song was written, Barry Sakharof and Rami Fortis, two of Israel’s foremost rock stars, reinterpreted the song in a style that was anything but nostalgic or romantic. More recently, DAM, an Arab/Palestinian hip hop group based in Lod, released a single called “Born Here” in Arabic and Hebrew. The song derives its lyrics and music from the song “Kan” (Here), using it to protest inequality and the frustration of being second-class citizens in their hometowns.

These two examples serve to highlight the role Israeli artists play in keeping us in check and in diagnosing the state of the nation and its people in creative and engaging ways. What can these examples teach us? What kinds of conversations and reflections can they prompt? How can we make them relevant to our students? How can we encourage our students to creatively express their own relationship with Israel? As the case study demonstrates, exploration of themes and values through the arts creates an engaging, interactive classroom by encouraging dialogue and interpretation.

The Ability to Engage

The arts bring the classroom environment alive; they create stimulating experiences by engaging students with various learning styles and expressions, thus motivating and inspiring each student. Depending on the construction of the lesson or unit, students can interact with the material on many levels, gaining aesthetic appreciation, engaging in critical thinking, analysis and interpretation, drawing meaning, understanding historical and cultural context, and actively participating in creative work.

While recognizing the importance of the integration of arts and culture in Israel education, it is unfortunate that little has been written on the subject; there are but a handful of curricular units in existence. The Internet, however, is an incredibly rich resource. In fact, all of the examples used here—from poems and video clips to visual art—were purposefully lifted from the Internet to demonstrate its potential as an accessible research tool.

In summary, bringing arts and culture into Israel education provides depth and context for students, helping them bridge the knowledge they have acquired on both the intellectual and experiential levels. History, geography, archaeology, and other fields are all invaluable in studying and making Israel real for students, but without the arts, Israel remains one-dimensional and distant. Infusing the curriculum with arts and culture brings Israel to life, making it relevant to today’s students, who experience life through their own culture and art. Our students connect to society through music, literature, dance, theater, visual art, and film—all of which show them to be parts of a larger whole.

As teachers, we have the capacity to engage our students in artistic exploration and creative expression. Imagine them gaining an appreciation of Israel and strengthening connections with their homeland while doing so. Go forth and unleash the power of art!

Endnotes

1 Dewey, John. Art as Experience. New York: Putnam, 1934. Print.

2 Hamlin, Jesse. “His photos are lovely, erotic, even a bit disturbing.” SF Gate. 2004. Web. http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/His-photos-arelovely-erotic-even-a-bit-2789869.php.

3 Bacri, Durar. “CV and Exhibitions.” Web. http://www.durarbacri.com/durar-bacri-cv-and-exhibitions/.

Vavi Toran was raised in Tel Aviv by a theatrical and artistic family and studied English Literature and Art History at the Hebrew University, and Painting and Drawing at the Bezalel Art Institute in Jerusalem. Vavi joined the Israel Center of the San Francisco-based Jewish Federation in 1996. As the Director of Cultural and Educational Resources of the organization, she helped fashion the Arts and Culture programs that have since become a model locally and nationally. In 2003 she was assigned the position of Director of the Israel Education Initiative, a joint project of the San Francisco-based BJE and the Israel Center. Today, Vavi is the Israel Arts and Culture Specialist at JewishLearningWorks in San Francisco.